In the previous newsletter, we looked at how Yves Citton defines power (as the flow of desire and belief) in his book Mythocracy: How Stories Shape Our Worlds.

In this newsletter, we will explore narrative as a form of power and examine how we can use it to benefit ourselves as managers.

As we concluded last time, we saw how others can influence our conduct by directing our attention to certain aspects and how that aligns with the flows of our desires and beliefs.

Narratives

When we talk about a narrative, we are talking about storytelling. We are discussing how something changes from one state to another. 1

There are six characteristics of narratives that Citton defines.

- “[A] narrative must describe a story that unfolds over time, with a beginning, a middle, and an end.” (65) A narrative is about transformation over time and takes place in time.

- There has to be “at least one main character (the protagonist)” and the narrative must be told from one or more specific points of view. (65)

- There needs to be at least an implied “causal consistency (which may be different from that of our actual world).” (65)

- There needs to be an implication of values upon the conditions of the transformation. Someone following the narrative will need to be able to invest “their desires and beliefs in terms of the supposed desires and beliefs of the story’s subject”. (65)

- “A narrative must both respect certain canonical norms that define its place within social discourses and institutions, and – at least for us modern adults – it must simultaneously provide an element of surprise, meaning that it cannot be entirely predictable just on the basis of these canonical norms.”(66) That is, it must be both relatable and understandable based on other things we have seen, heard, or read, and it must be different enough to have an element of surprise.

- Finally, a narrative must have “the ability to distil the hypercomplexity of reality into a schematic, unifying imaginary model.” (66) In other words, a narrative needs to have enough complexity to feel like a glimpse into a real world, but also must be in a model that is coherent and makes sense.

Thus, narrative can capture our emotions and change how we think about values. It provides a structure that allows us to integrate many different perspectives in a way that enables us to find our bearings. “[i]t is by narrating the events of my life that I make sense of them. That is, I give meaning to these events by setting them in an interconnected sequence of (possible or actual) facts, in which I believe I can identify relationships of causality, incompatibility, convergence, and divergence.” (67)

Narratives provide frames through which we can see and make sense of the world, and they help explain the nature of causality and transformation. We carry a story about each and every transformation and change that happens. Our narratives create the frame through which we understand those changes. (68)

We do this for ourselves both as individuals and collectively. And the stories we tell act as “machines for orienting our own flows of desires and beliefs.” (68)

Citton examines “Paul Ricœur’s theory of mimesis,” which reveals the three distinct moments of comprehension that occur when viewing a narrative. The first is through pre-comprehension, where we find and recognize the parts of the story that we recognize as familiar. The second is immersing ourselves in the world of the narrative based on that familiarity. Finally, the parts that are unfamiliar cause a “reconfiguration of our habitual ways of linking together facts and deeds.” (68-69)

From this, Citton claims that our power lies “in our ability to arrange in different sequences 1) the images, thoughts, affects, desires, and beliefs that we associate in our minds, 2) the phrases that come out of our mouths, and 3) the movements that emanate from our bodies.” (69-70) In other words, our power comes from narrating our lives by changing how we link ideas, tell our stories, and act in the world. We are always telling ourselves stories. “There is nothing inherently wrong with ‘telling ourselves stories’: it all depends on what the stories are doing.” (71)

But we don’t tell ourselves stories in a vacuum. We often draw inspiration from stories we already know. 2 It is essential to recognize that just because people are familiar with the same narrative doesn’t mean that they will then see it the same way, as every story we encounter is interpreted through the lens of our specific situation and context. (74-76)

Storytelling to scripting

People always tell stories for a purpose; it could be simply to entertain, but it might also be to elicit some action. And while stories themselves may not always be true, “the act of telling it is always a real act, directed towards certain objectives that motivate and condition it.” (82)

Here, it is important to introduce the idea of scripting. Or telling stories in such a way to try to create a reality. It imagines other real people as fictional characters and attempts to have them behave in a specific way. (82)

This is a standard plot device in fiction. I recently read Starter Villain by John Scalzi, and one of the main characters, Anton Dobrev, induces the protagonist, Charlie Fitzer, to behave in a certain way to create a specific outcome. Charlie and the reader have no idea that this other character is scripting what is happening. Charlie believes he is acting of his own free will, and in a way, he is. However, the conditions have been set up in a specific way to get him to behave as he does. 3

Scripting, surely, is a matter of projection, foresight, and anticipation – a matter of programming: writing the future ahead of time – and yet, it always includes an element of improvisation, trial and error, and constant rearrangements and readjustments. This process goes on as a story unfolds whose parameters are largely beyond our control, since we are striving to meta-conduct free subjects’ conducts…We can see that the work of scripting, when pushed to its logical limit, transforms every act into a gesture: since soft power consists in making others act of their own free will, we must neither resort to open violence nor stick immediately to who we are, but modulate appearances so as to produce the hints and prompts that will lead the other person to do what we want them to want to do. (91)

In Starter Villain, almost everything goes according to the script, but certain events are unaccounted for. For example, Anton (nor anyone else) could have seen that Charlie would support the unionization of the dolphins. With scripting, there is always room for improvisation. Not everything can be forced to go exactly as planned, but the script meta-conducts people’s behaviors.

This works, in part, because there are pre-existing social and individual desires and beliefs, as Citton states.

The art of storytelling is all about capturing (pre-existing) desires and beliefs in order to attach them to oneself and bend them to one’s own advantage. The whole focus of storytelling, then, is to invent what the reader wants to hear (95)

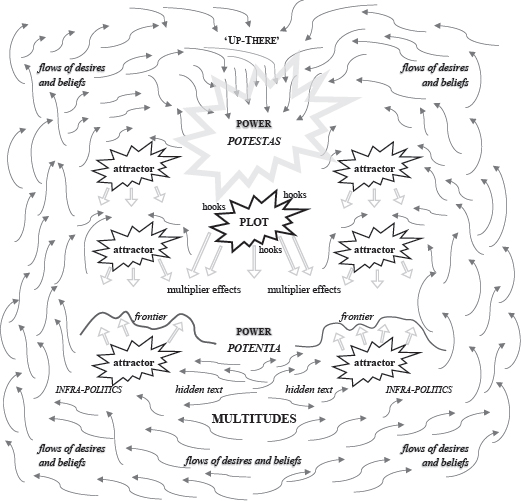

Attractors

How do we attract people’s attention to “capture the flows of desires and beliefs”? (99)

Citton writes that we use “attractors” to get and maintain people’s attention. He names two primary attractors: the hook and the plot.

Most of us are familiar with hooks. It often can refer to the catchy part of a song, or the initial part of a headline or social media post designed to get our attention, but it can also be the cover of a book, the poster or trailer for a movie. But how do those work? If you see any influencers on LinkedIn, you will notice some common patterns, and those patterns do work. The reason they grab our attention is not really the content, but that we identify the “styles of expression and communication.” (100)

When we see “My client just doubled their monthly recurring revenue. Here’s how I helped them do it,” we know the genre of that post; it is going to be a simple, step-by-step guide to driving revenue. What makes it sticky is that we recognize the form.

The second type of attractor is the plot, which is how the parts of the story are tied together to form a whole. The plot needs to match the genre expectations set up by the hook.

What makes attractors, both hooks and plots, work is that we recognize them in relation to patterns that we have seen before. And so when we are trying to do something new we often need to “attract the attractors” to make any new form of narrative appealing. (105)

There are two types of plots: those that reiterate what is already known and those that reconfigure what is known into something new. We may be tempted to see reiteration as tending towards stability. But Citton warns us against thinking in binary terms and rather to ask “in what precise direction a given plot pushes its audience at a given moment in its development.” (108)

We shouldn’t look at just whether the plot reiterates what we know or challenges us. We should also see the nature of the conflict it draws us into. When our attention is captured, we usually take sides in the conflict. (110)

There are five key ways that we are led to take sides:

- The transition that structures the narrative may portray the change as positive or negative based on what is gained or lost through that transition. This can lead us to see one state, either the prior or latter, as better preferred and determine how we feel about the subject.

- There is usually a polarization between the subject of a narrative and an opponent, which can lead us to take sides.

- Different sets of values conflict in the narrative, and those can push us to take sides.

- How the story is narrated can also sway our allegiance from one side or the other.

- The belief system we carry into the engagement with a story will also determine which side we take. (110-111)

It is because what we desire and believe are so intertwined that “we desire what we believe to be good and, as Spinoza pointed out, we believe that what we desire is good.“(110)

Narrative activity thus reconditions our economies of affects…the narratives we consume on a daily basis that (constantly) fabricate the value systems which accompany and drive the evolutions of our societies. Narrative machines are the site where we (re)evaluate the values in whose name we claim to direct our behaviour. (112)

What we feel and what we believe are conditioned by the endless narratives that we constantly consume. It is through narratives that “we (re)evaluate the values in whose name we claim to direct our behaviour.” (112)

What makes narrative powerful is that “the stories I hear today condition the way I will react to something tomorrow, in a month’s time, or in twenty years.” (109)

Our stories all take place in a context. One way to look at that context would be through the lens of dominated groups. Or groups that aren’t those in power. From this perspective, Citton evokes James C. Scott, who proposed 4 types of storytelling (or discourse) that can happen.

- The public transcript “corresponding to ‘the self-portrait of dominant elites as they would have themselves seen’ and which is ‘designed to be impressive, to affirm and naturalize the power of dominant elites, and to conceal or euphemize the dirty linen of their rule’.” (120-121)

- There is also the hidden transcript, which “takes place offstage”, beyond direct observation by powerholders, and which consists of ‘speeches, gestures, and practices that confirm, contradict, or inflect what appears in the public transcript’” (121)

- Similar to the hidden transcript is the “‘politics of disguise and anonymity’” which is a form of subtle rebellion. It is not fully hidden, appearing in rumors and jokes, but it remains opaque.

- Finally, the “’Saturnalia of power’” is when something breaks through the gap between the hidden and public transcript and speaks truth to power. This type of thing is usually repressed immediately.

To ground this in our notion of power.

If we conceive of power as arising from the circulation of flows of desires and beliefs, what we then understood to be points of leverage with multiplier effects (institutions) now turn out to qualify the attractors (hooks and plots) defined above. An institution can function only insofar as it is constantly fed by the flows of desires and beliefs (yearnings, fears, hopes, hatreds) of the human beings it is dealing with. It can mobilise these flows of desires and beliefs only insofar as it succeeds in attracting them with some desirable and credible story. (122)

Institutions (including individuals in institutional roles, such as managers) can only exert power if they can attract attention with a “desirable and credible story” to shape the desires and beliefs of the people they interact with.

Citton provides this diagram to show how these components interact.

There is an ongoing power struggle between the hidden transcripts that long to be heard and the public transcript, which doesn’t want to lose its position of dominance. The pressure in this space between the hidden and public transcripts is the space of Mythocracy, the power of myth.

Demand for Equality

Everyone has the ability to tell stories and thus “imagining, inventing, and affirming various forms of life” (129). But we all know that differing levels of abilities to tell stories create inequalities in social life.. The question then becomes, how do we create more of an equal opportunity for everyone to use this power?

There are three challenges to making this power more broadly available:

- The initial challenge is to recognize that power is always power that is borrowed from the people you will have power over, and as a result, that power is fragile. And because that power is taken from the masses it seems like something that the masses control and therefor not having it is related to a choice of the masses.

- The inequality is the nature of scripting and narrative and this can be a challenge to accept. There is a desire to see everyone as born equal, but we are not. We “are all ‘born different’ and in different contexts which change what is possible for each of us based on that context. This inequality doesn’t need to hold us back, it can instead be used in a way that “emancipates rather than enslaves us”. (131)

- The final challenge is “to build institutions in which the inequalities between different levels make it possible to mediate the self-affection of the multitude in the direction of a common and egalitarian empowerment.” In other words, the challenge is not to accept the power imbalance, but rather to create structures and use those structures to give voice to more people. (130-132)

Let us imagine the value of the hierarchy in management as an example (Citton uses the classroom as an example, but I am going to try to change it for our purposes). A manager’s goal is to help a team achieve and be the best they can individually and collectively.

One approach to this is to act as an authority and “script the relationship as one of obedience” (132). This comes from a desire to be the sole bearer of some broader view of the organization, its needs, and precious experience, which is guarded and shared with those who obey. Some managers take this approach, who see their expertise as key to their position, and they want to make all the decisions and have things done their way.

An alternate approach is to bring the team together to make sense of and shape the team’s direction collaboratively. This doesn’t mean the inequality between the manager and the team is vanquished. The manager remains in a role of scripting and guiding the team. What is equalized is not the role or the power itself, but the validity and capability of intelligence.

This isn’t to say a manager doesn’t have more knowledge, skill, or experience, which puts them into the managerial position; I believe they should. But that inequality is not, on its own, problematic. The real issue is whether that inequality leads to drastically different consequences and benefits. The power to script is less the skills in storytelling, and more the position of authority from which to be able to control the “circulation of words, ideas, and images.” (135-136)

What matters is how that position of power is used and the narratives and scripts given attention as a result. Part of this is letting others tell stories and ensuring those narratives are heard.

One important final point about narrative is that, as Citton quotes from Walter Benjamin:

Every morning, news reaches us from around the globe. And yet we lack remarkable stories. Why is this the case? It is because no incidents reach us any longer not already permeated with explanations. In other words: almost nothing occurs to the story’s benefit anymore, but instead it all serves information. In fact, at least half of the art of storytelling consists in keeping one’s tale free of explanation.3 (148-149)

Part of what makes storytelling powerful is the opening it leaves for interpretation. Events, information, and data have meaning because of the narrative we can place them in. Narratives allow for many potential explanations. (149)

This process is often lost on managers. We try to explain how things work and laden our narratives with explanations. The goal is not to give explanations but to “pose other questions.” Too often, we take what is given without question, and by taking what is given, we lose what is possible that can be imagined. As managers, we need to leave a gap so that other ways of being can be realized. (171)

We shouldn’t see the expert or the manager as an enemy. They are merely doing their best in their context, but we should see that there is something to fight against in the authoritarian ways that those with power often control the narrative. (183-184)

And so the point of stories is nothing short of an experiment. As Citton writes,

This experiment is about the way we see our world and the way in which we can put into myths – into stories and into enchanting words – the demands made on us, the beliefs that run through us, and the desires that drive us. Precisely the power of such myths is that they enable us to reach other possible worlds. (189)

What does this mean for managers?

As a manager, your role is twofold:

- To use your power to elevate the voices of others. It is easy to believe that the organization gives you the power you have. It is not given by the people over whom you have power. If they are willing to give you that power, it is not necessarily because you earned it; it is also because of the context your employees are in, where giving you power is preferable to other outcomes. How you use that power is then vital. Use it to raise those voices.

- To tell narratives and stories to open up possibilities and allow others to envision possible new worlds. Often, as a manager, you are in a position to tell your team about things that are happening elsewhere in the organization. In those moments, it can be more powerful to follow the guidance of Benjamin and leave out the explanations. Tell the stories in a way that is open to how they can interpret it, and allow narratives that challenge what is given.

The Mythocracy is what you never came to be that you should be. – Sun Ra

- Citton, Yves and David, Broder. Mythocracy: How Stories Shape Our Worlds London: Verso, 2025. p 64 – All future citations will have the page number inline in parentheses. ↩

- This is what Bernard Stiefler refers to as tertiary retentions. Primary is the in-the-moment awareness of an event, secondary are what we recall after the fact, and tertiary are those which are memories from others transmitted through stories. (73) ↩

- Although one can see how there are really two levels of scripting that the author took in writing the book, and second, how a character causes another character to act in a certain way. Our focus is on this second form of scripting. ↩