The recent rounds of layoffs, which have hit middle managers particularly hard, have raised an important question. 1

Do we even need middle managers anymore?

On one side, companies have flattened their hierarchies, and the managers they retain are asked to have more direct reports than they previously had. In some ways, this makes sense if you are not planning to do much hiring. In times of rapid growth, more managers can speed up hiring. In times of slower growth, managers can devote more time and energy to their team and can take on more direct reports (to an extent).

On the other side, progressive organizations are eliminating management with the stated aim of creating more empowered individuals and teams by focusing on self-management and have gone so far as to call management a disease. 2

It’s no wonder that middle managers are more stressed and overwhelmed than ever. In 2023, HBR reported that more than 50% of managers felt burned out, and that has likely only worsened.

While both the progressive employee empowerment movement and the efficiency shareholder value movement may share a common goal, it is more likely that there is something that needs to be teased apart. There is more risk to this than it seems.

What do managers do

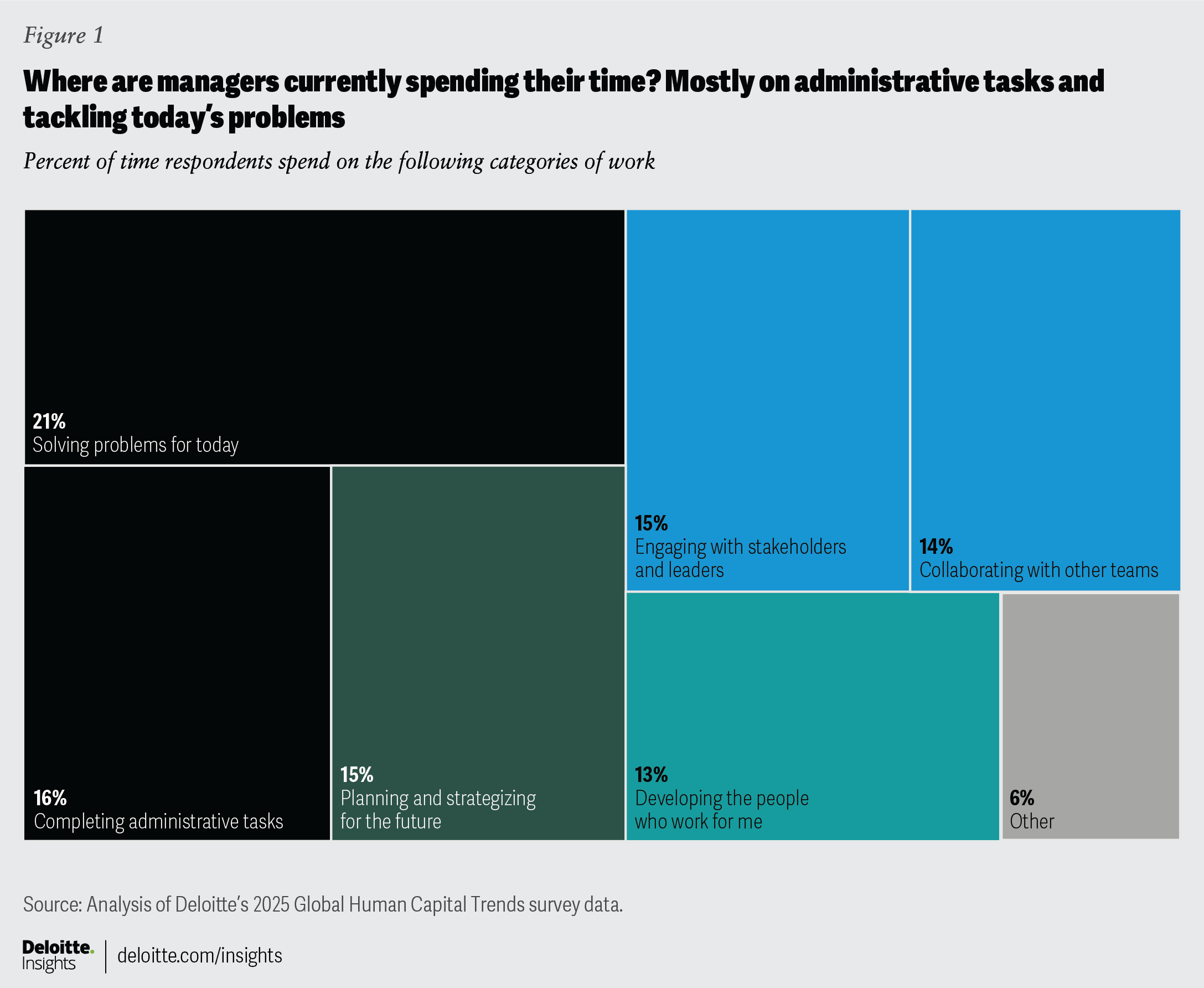

According to Deloitte, managers spend most of their time solving today’s problems, handling administrative tasks, and engaging with other stakeholders and leaders. 3

That is, management is primarily an operational role, with a subset of the time 15% spent on thinking about the future and 13% developing the team. And despite all the talk about management being about strategy and growing people, the reality of these numbers seems pretty accurate based on my experiences.

Which makes it worth going back even further to see where management originated.

Marx spells this out well (quoted in Jacobin):

The labour of supervision and management is naturally required wherever the direct process of production assumes the form of a combined social process, and not of the isolated labour of independent producers. However, it has a double nature. On the one hand, all labour in which many individuals co-operate necessarily requires a commanding will to co-ordinate and unify the process . . . much like that of an orchestra conductor. This is a productive job, which must be performed in every combined mode of production.

On the other hand . . . supervision work necessarily arises in all modes of production based on the antithesis between the labourer, as the direct producer, and the owner of the means of production. The greater this antagonism, the greater the role played by supervision. Hence it reaches its peak in the slave system. But it is indispensable also in the capitalist mode of production, since the production process in it is simultaneously a process by which the capitalist consumes labour-power. 4

Thus, management plays essentially two key roles for Marx.

- Coordination of teams to support collaboration among team members.

- As a mediation layer between those who run the corporation and those who are doing the work. The primary function is to smooth over the inherent conflicts between those who want as much work as possible accomplished and those who would prefer to do as little as possible.

While Marx places the extreme end of this second point at slave labor, the other end would likely be when employees themselves own the company and the means of production, and are thus reaping the full reward for the work they do. In such cases, the interests of those who own the company and those who work in it are one and the same.

Looked at from this lens, it would make sense to eliminate managers when employees fully own the firms themselves. This is perhaps the central position of the more progressive management elimination movements. The idea is that if people are self-managing, they become like owners and no longer need the oversight. I think that can make sense when those employees truly have a controlling ownership in the firm, but that is not usually the case today, and it doesn’t fully take into account other trends that we have seen over the last few decades.

Self-exploitation

However, another bit of historical context is also worth looking at. It is quite common today for companies to focus on things like mission and vision statements, which create a noble cause with the goal that employees will align themselves with that cause and thus see themselves as being in alignment with the business itself. This leads to the perception of decreased antagonism, as it appears that everyone is on the same side and distracts from the reality that working for that cause is enriching some with generational wealth, while others may be living paycheck to paycheck.

We also live in an achievement society in which, as Byung-Chul Han has pointed out,

“The achievement-subject gives itself over to freestanding compulsion in order to maximize performance. In this way, it exploits itself. Auto-exploitation is more efficient than allo-exploitation because a deceptive feeling of freedom accompanies it. The exploiter is simultaneously the exploited. Exploitation now occurs without domination. That is what makes self-exploitation so efficient.” 5

We believe we are working in our own best interests, and therefore, we are compelled to give as much as possible, which ultimately leads to burnout. We are striving for the next raise and promotion, and we continually compete and strive to improve our performance. In this way, we no longer need managers to push us; we are doing it to ourselves.

This is a lens that makes the move to eliminate managers for efficiency make sense.

However, in addition to this role, middle management also plays an ideological role, which becomes apparent when viewed through the lens of the Professional Managerial Class.

Professional Managerial Class

As a middle manager, you are in an interesting position; you aren’t part of the executive leadership team that is making all the decisions and who are poised to benefit most from the performance of the company (in terms of stock and other incentives) at the same time, you have access to more information and power than the average worker or even line manager.

There was a term created in the 1970s by Barbara and John Ehrenreich, which is the professional managerial class, which they define as:

We define the Professional-Managerial Class as consisting of salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations. 6

This, in many ways, describes the role of middle managers. 7

And while we may not often think in terms of the language of class struggle, we are usually aware that those with management responsibilities carry different burdens relative to the business than individual contributors do, and that they hold positions of power. Often, they are the ones making decisions about who is retained and who is laid off during reorganizations. (Although they usually lack the power to initiate or stop a reorganization from occurring, they merely operationalize a decision that was already made.)

At the same time, they may see themselves as a voice for their teams and speaking up for the team’s accomplishments, and in this way, middle managers are responsible for a form of mediation layer.

Mediation

One other common characteristic of our time is a sense of immediacy. At its simplest, Immediacy is the lack of mediation. 8

“mediation” means the active process of relating—making sense and making meaning by inlaying into medium; making middles that merge extremes; making available in language and image and rhythm the supervalent abstractions otherwise unavailable to our sensuous perception—like “justice” or “value.” 9

And this has often been the role from the perspective of the Professional Managerial Class.

When a significant change is communicated from senior leadership, the role of a manager is often to make it understandable and palatable to the team.

In this era with constant priority shifts, reorganizations, and unclear direction, employees can feel lost and confused. Often, the role of management is seen as helping employees understand the changes and adapt quickly to keep the team as productive as possible.

Why do managers feel the need to protect the team? They are adults. We often want to create a sense of security. But who does this false security serve?

It isn’t the team; sure, they may feel better momentarily, but that only begins to erode the trust they have in you. Managers often feel like they are protecting the team, but really, they are protecting the business.

The future of middle management.

To summarize, the historical perspective on management, including a view of what managers do today, shows the key roles as:

- Pushing to maximize the output of the team and work as effectively as possible.

- Helping translate the needs of the leadership team to the workers so that they remain committed and engaged in the work.

The path forward is through mediation, but in a new way. When people become managers and begin to see their role clearly, they become aware of their structural position of power, and while many do, they may not know how to handle it effectively. As Freire points out in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the result is often a form of paternalism. Managers want to treat their team like their own children or family and protect them. However, that maintains the dynamic that can be troublesome.

“Discovering himself to be an oppressor may cause considerable anguish, but it does not necessarily lead to solidarity with the oppressed. Rationalizing his guilt through paternalistic treatment of the oppressed, all the while holding them fast in a position of dependence, will not do. Solidarity requires that one enter into the situation of those with whom one is solidary; it is a radical posture.” 10

We might not perceive people on our team as oppressed, but it is helpful to consider how Freire defines oppression: “An act is oppressive only when it prevents people from being more fully human.” 11 From this perspective, we can see how often in our work roles, elements of our humanity are set aside as we are treated as “resources,” “human capital,” or, to use Marx’s term, “labor power.”

If there is to be a future for middle management that supports individuals and makes sense for organizations, it needs to be a form of radical solidarity with employees. One that allows people at work to be fully human.

Most people I have spoken with genuinely want to do great work, and they desire an environment that respects them. They want to be able to express their human creative side in a way that doesn’t entrap them in endless productivity and efficiency hamster wheels. Managers can help create an environment that fosters individual and team growth. And this is perhaps the hardest thing for managers to let go of: the drive to have employees improve and grow in the way you want them to, or to limit their options within the definition of their roles. And while this may seem employee-centric, companies will benefit as employees are more engaged and happier at work.

I think Freire explains the task well:

A revolutionary leadership must accordingly practice co-intentional education. Teachers and students (leadership and people), co-intent on reality, are both Subjects, not only in the task of unveiling that reality, and thereby coming to know it critically, but in the task of re-creating that knowledge. As they attain this knowledge of reality through common reflection and action, they discover themselves as its permanent re-creators. In this way, the presence of the oppressed in the struggle for their liberation will be what it should be: not pseudo-participation, but committed involvement. 12

Following this idea, I would suggest that the future of middle management is to fill these key roles:

- They are experts who come with knowledge not to implant it in employees, but to engage in conversation with them and use that experience to help employees discover a broader perspective.

- They help the team make sense of the directions and changes that come from senior leadership. Not to make it more palatable or to soften the rough edges, but to reflect critically, and collectively navigate and respond within the realistic constraints.

- They are the representatives of their teams. Acting as a voice for the team with senior leadership.

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/chriswestfall/2024/12/19/white-collar-job-cuts-middle-management-decline/ ↩

- https://www.corporate-rebels.com/blog/management-is-a-disease-heres-the-cure ↩

- https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/human-capital-trends.html#role-of-managers ↩

- https://jacobin.com/2020/07/karl-marx-capital-corporation-production-socialism ↩

- Han, Byung-Chul. The Burnout Society. Stanford University Press, 2015 ↩

- Walker, Pat, editor. Between Labor and Capital. South End Press, 1979. ↩

- I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that Barbara and John Ehrenreich saw the Professional Managerial class, or PMC, as broader than that and it included much more than just middle managers. In fact, if you think about it from the context of Ideological State Apparatuses as defined by Althusser, most of those Apparatuses are operated by the PMC. I talked about Althusser in this post. (https://www.evolutioncoach.org/blog/2024/10/18/stuck-in-the-middle-9-ideology-by-althusser/) ↩

- This is covered in more detail in this post: https://www.evolutioncoach.org/blog/2024/11/08/sitm-12-immediacy/ ↩

- Kornbluh, Anna. Immediacy, or The Style of Too Late Capitalism Verso, 2024. ↩

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 50th Anniversary ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩